We’ve all heard it before. A child’s zip code should not determine the quality of education they receive. We’ve sat through or read numerous pieces on why we cannot continue to allow zip codes to determine the success of our children. I agree. I believe with my whole heart that every child deserves a quality educational experience that allows him or her to reach their highest potential. However, it almost seems silly for us to reduce the well known inequity students experience to geography and zip codes. We need to go beyond the idea that location of where you receive your education matters and dig deep into the mindsets that hold some communities hostage in the fight for equity.

I guess my frustration with the zip code argument is that there is nothing one can do, no action a student can take, to change where he or she lives. Additionally, seeking teachers or educational leaders who are “beating the odds” signifies that we’ve given up on changing mindsets, on creating more equitable communities, on calling out White flight and segregation academies meant to keep children separated during the time they spend in school. All the zip code rhetoric in the world doesn’t answer these questions:

1. Why can’t all of our students attend a quality school together?

2. Why can’t we pool our resources and provide a great education for every child instead of spreading resources and opportunities thin because there are separate systems of schooling (both formally and informally)?

In Mark Elgart’s 2016 Huffington Post article, Student Success Comes Down To Zip Code, he shares:

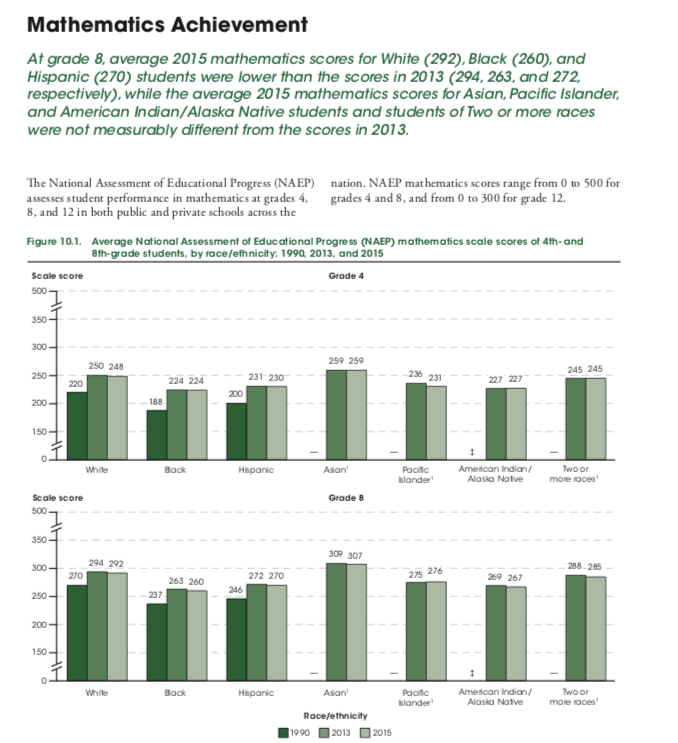

A study recently released by sociologist Ann Owens of the University of Southern California showed that access to good schools in the nation’s 100 largest cities continues to exacerbate income inequality between neighborhoods. Income disparities in communities increased by 20 percent from 1990 to 2010, largely because of the desire people have to live within the boundaries of top-performing schools. The study also indicates that income segregation between neighborhoods was nearly twice as high among households that have children compared to those without.

Instead of talking about the impact of zip codes and residential location on school quality, why isn’t there more conversation around who is drawing attendance lines that exacerbate inequity? Why aren’t we discussing how we can create more mixed income neighborhoods? What’s keeping us from talking about the root causes of the income disparities this researcher speaks of and how we begin changing that?

Zip codes aren’t the problem. It’s the mindsets of those who have forgotten or either don’t believe that the public education of all children is for the public good of all of us. As long as we champion a “beat the odds” mentality instead of a “level the playing field one” the zip code narrative will hold true. While I applaud every student who overcomes the obstacles of poverty and trauma, and every educator who is able to help students be successful in spite of the obstacles they face, wouldn’t it prove helpful to work on reducing the disparities and obstacles instead of giving all of our energy and attention to how we overcome them? If we were to spend more time addressing the causes instead of the effects, perhaps we might be able to shift this conversation to one that boldly and courageously addresses what we’ve known to be a key issue in our work since James Coleman’s 1966 report: We are better together. Coleman notes,

The research results indicate that a child’s performance, especially a working-class child’s performance, is greatly benefited by his going to school with children who come from different backgrounds,” Coleman said. “If you integrate children of different backgrounds and socioeconomics, kids perform better.”

We have an opportunity before us as educators to call on policy makers and others who make decisions about economic development, jobs, quality housing, and more to help reduce the inequities that plague these areas where zip codes are credited for the lack of success children experience. If we know we are better together, that all of our children are better when we educate them together, let’s stop talking about zip codes and start talking about how we can live, work, and learn together for the benefit of all involved.

Until next time- Be you. Be true. Be a hope builder!

Latoya